Access full report

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

Facilitated by The Modern Data Company in collaboration with the Modern Data 101 Community

Latest reads...

TABLE OF CONTENT

As a law of product approach, we will start with the user and understand what’s going on in their mind:

Everything is manual; teams are working nights, weekends, and holidays because there are numerous data pipelines that are interdependent. Data engineers are constantly on call asking, “Is your pipeline running now? Because mine will run at 2:15. I can’t sleep until yours is done.”

The user down the dependency chain is always nervous because they have to meet SLAs, and whether they will be able to meet them or not depends on upstream pipelines, which are beyond their control.

POV of the person running the upstream pipeline is not helpful:

“Yes I’m working on it, but it’s so late in the night. Why don’t you put a check in, why should I be responsible for your pipelines?”

All are responsible for their own KRAs (Key Responsibility Areas). Often, data engineers are NOT responsible or accountable for the consequences of dependent pipelines owned by other pods/engineers/teams.

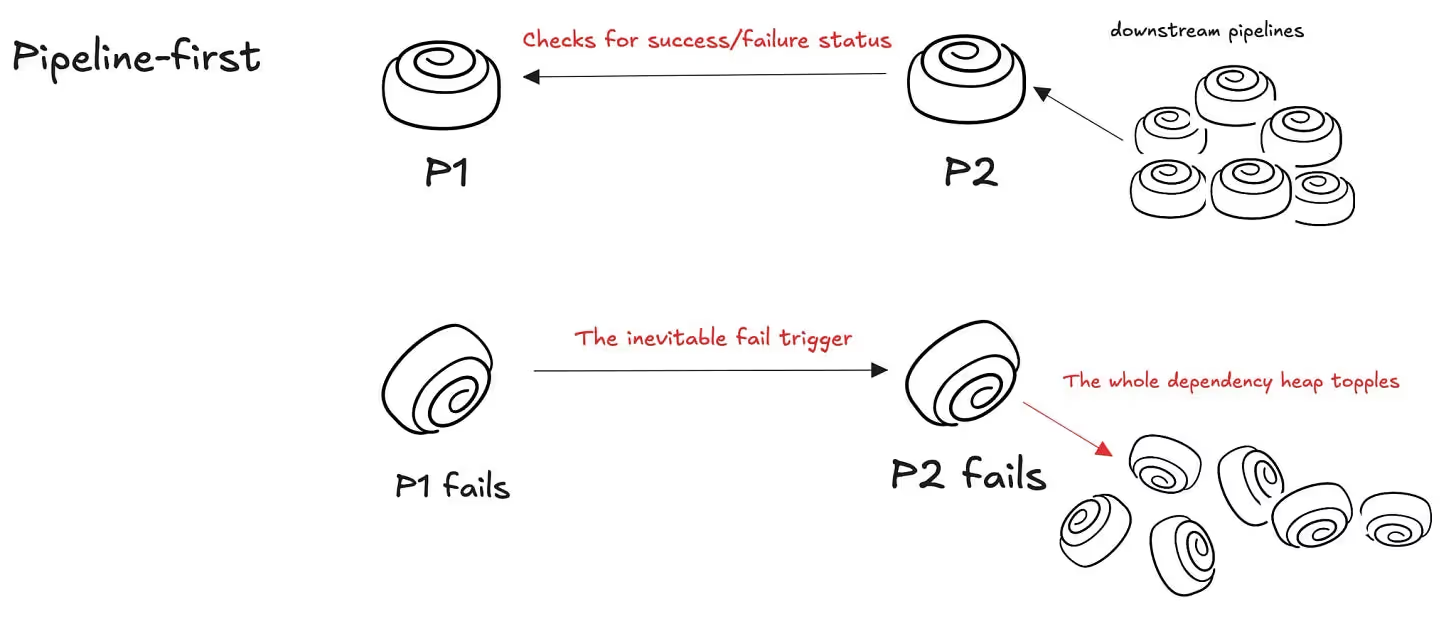

If pipeline 1 breaks, that implies the inevitability of failure in pipelines 2, 3,…, n; it’s like saying, “a banana peel is on the floor, so we have to fall now!” 🍌

The pipeline-first way of working with data is synonymous with a fail-first way of working with data.

When we think or say that a unified data platform gives these users a more resilient foundation to work on, we are considering how it solves the pipeline dependency problem: enabling users to NOT consider failures or successes of pipelines as events that make or break their SLAs. Just a means to an end. We’ll break this down soon.

But first, some semantics. “Resiliency” is an overloaded word. All data systems and technologies have been described as resilient in some form or shape for decades in the enterprise space. While the concept holds immense value, the vocabulary is saturated.

The significance of semantics is immense, as we see in data technologies, and it’s the same when it comes to the way we talk about technology. To grasp the value of resilience in data systems today, we need to break down and understand how and exactly why these systems become resilient.

When you start putting pipelines first, what we call a “Pipeline-first” approach, you’re effectively working with a pre-cloud mindset. That era, the data centre era, was defined by physical hardware. Machines were stable and rarely failed. Failures were exceptions, not norms. The system was, therefore, built around it: to handle the exception.

Even in Amazon’s early days, the large hardware rarely went down. But that’s not the whole story. Virtual machines (VMs) would come and go on those machines. They’d move around.

What changed with the cloud era wasn’t the nodes; it was how we used them.We began scheduling workloads on ephemeral resources. Suddenly, your code had to be ready to fail, quickly and gracefully.

The cloud is designed around this. It expects things to fail, and fail often, but in small, isolated, recoverable ways. So instead of pretending nothing breaks, you build systems that expect it. You try. You catch. You retry. You defend.

Which means: pipelines will fail. Not because something went wrong in the traditional sense, but because resources weren’t available right then. That’s not failure; that’s design. Try again later.

If you take a pipeline-first view: P1 runs, then P2, then P3, and so on; you’ve built a tower of dependencies. If P1 fails, the whole chain waits. You’ve introduced artificial coupling. A cascade of failures, not because the data isn’t there, but because your orchestration is rigid.

Put data at the centre, not processes.

Say you’re enriching transactional data with weather info. Let’s say the weather data comes from weather.com. P1 pulls the weather data. P2 enriches the transactions. In pipeline-first logic, if P1 fails, P2 fails. Then everything else waits.

But if you think in data-first terms, P2 becomes intelligent.

No panic. No failure. Just… pause. A calm system that has not burnt itself out.

P2 didn’t fail. It just didn’t find the input it needed yet. It’ll try again. It’s decoupled from P1’s timing or retry logic. It behaves more like a thinking agent than a dumb task on a schedule.

Pipeline-first thinking leads to brittle orchestration. Data-first thinking leads to adaptive, fault-tolerant systems. It’s a way of thinking: you’re putting data first instead of processes first.

Let’s reframe the way we think about data work. Before you ever get to processing, you’re in the world of preprocessing. This is the unglamorous but necessary part. Maybe it’s a mess of CSVs. Maybe PDFs. Maybe images.

You’re not building data products yet; you’re staging.

Preprocessing is about shaping raw material. You might extract EXIF metadata from images, grab GPS coordinates, timestamps, and structure chaos into something usable. That’s your source-aligned data product.

It’s not yet for consumers, but it’s aligned to the source, clean, structured, auditable.

From there, you move to the consumer-aligned data product: something a downstream user or system can actually act on. This is where pipelines show up. In some cases, especially early on, you do need to think left-to-right: take input, do something, move it forward.

Once your data has been shaped into a source-aligned format, the need to think “pipeline-first” disappears.

That’s why we’re not spending time glorifying preprocessing. It’s table stakes. We acknowledge it, we support it, and we retain the construct in the unified platform spec.

But the conversation we want to have is: What if you didn’t have to think about pipelines at all?

The goal isn’t to ensure pipelines don’t exist or never fail. The goal is to ensure the system doesn’t care if they do.

But how do we make a system that doesn’t get impacted by failing events? Or even succeeding events?

The whole design we build is more defensive, more guardrailed.

The word defense comes from the Latin defensare, meaning to ward off, to protect persistently. Defensive programming, then, is the persistent act of protecting your system from collapse; not just technical failure, but epistemic failure: wrong assumptions, vague specs, or future changes in context.

Defensive programming begins with a simple premise: never trust the world. A system designed not to trust and work around mistrust. And in defending against mistrust, the system creates a more trustworthy, reliable, or resilient layer for citizens operating on top of it.

In other words, you delegate the brunt of mistrust to the foundational platform to have the luxury of a trusting and relaxing experience.

The system wouldn’t spare any entity in its mistrust. Not your users. Not your dependencies. Not even your future self. Because somewhere, somehow, assumptions will break. Systems will lie. Users will be lazy. Inputs will surprise. And in those moments, the code that survives is the code that was written with doubt, with discipline, and with design for failure.

Here’s a recent conversation on the same that adds good perspective on the value of defensive design for data systems, such as ones that could host data or AI apps at scale for cross-domain operations.

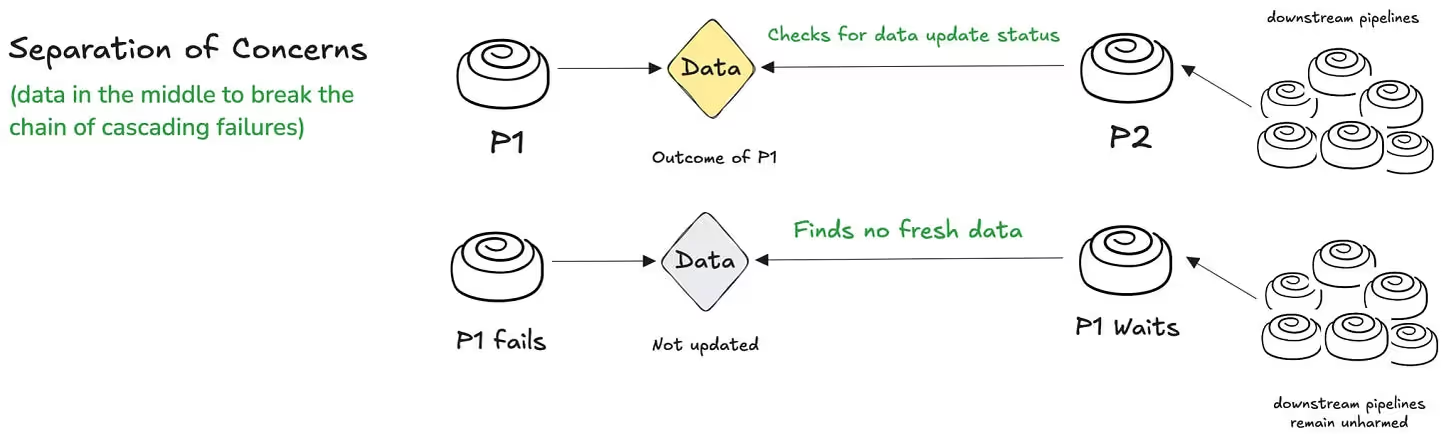

Let’s go back to the conversation of pipeline-first vs. data-first. In pipeline-first, the failure of P1 implies the inevitable failure of P2, P3, P4, and so on…

In data first, as we saw earlier, P2 doesn’t fail on the failure of an upstream pipeline, but instead checks the freshness of the output from upstream pipelines.

Case 1: There’s fresh data. P2 carries on.

Case 2: There’s no fresh data. P2 waits. P2 doesn’t fail and trigger a chain of failures in downstream pipelines. It avoids sending a pulse of panic and anxiety across the stakeholder chain.

In data systems, defensive programming is not just about protecting your pipelines from the cascading impact of failure, but also protecting your system from assumptions.

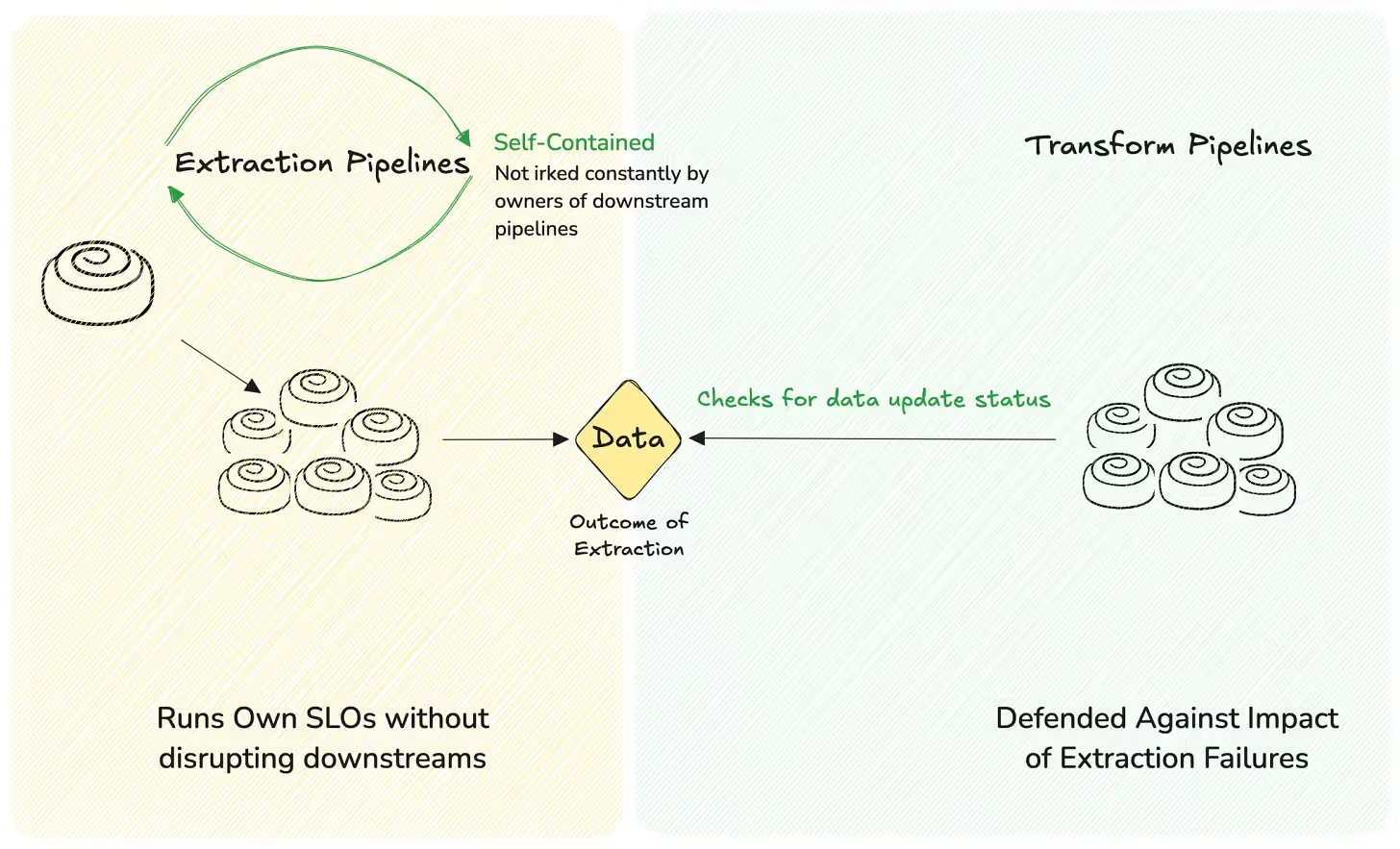

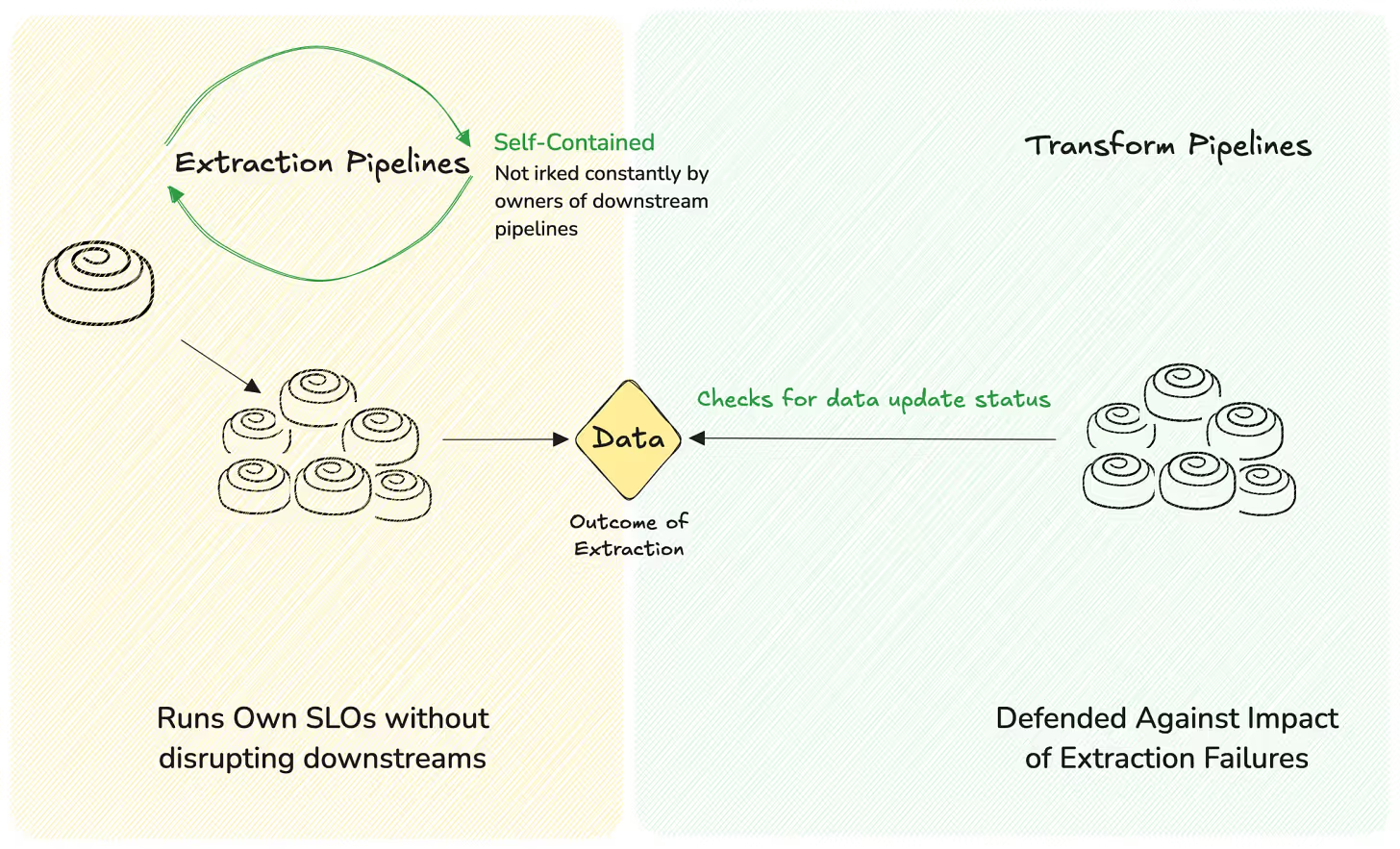

And one of the most detrimental assumptions in modern data systems? That extraction and transformation belong in the same pipeline. They don’t.

The implication is that transformation shouldn’t be tightly coupled with extraction jobs or pipelines because of the same reasons we’ve discussed so far. Defending against cascading failures because one job failed.

Extraction and transformation are not the same unit.

Writing them together in a tight little script may feel efficient. However, efficiency is not measured in lines of code but in resilience. This script is potentially failing far more times than a decoupled script.

Sometimes, writing more code buys you more reliability.

A defensive guardrailled system would furnish tools for extraction and transformation accordingly. The toolkit for extraction will not give you transformation options. Transform tools wouldn’t provide an extraction option.

So it’ll enforce the guardrail in a way that you’re propelled to think in this logic, and consequently, bask in the luxury of trust built on a defensive foundation.

In this defensive platform ecosystem, data is the decoupling layer.

We don’t tie transformation logic to the act of extraction. We don’t let transformation fail just because data didn’t arrive at 3:07 AM. Instead, our transformation pipelines ask a straightforward question: “Is the data ready?”

If yes, they run. If not, they wait. They don’t trigger a failure cascade. They don’t tank SLOs.

Most tooling today nudges people toward pipeline-first design. Where one failure ripples through dozens of downstream steps. Not because the logic is wrong, but because the design didn’t defend itself.

Your architecture mirrors your product. Your product mirrors your organisational thinking. So if your platform is pipeline-first, you end up with a pipeline-chained org.

Ergo, we go data-first architecture to become a data-first org.

Thanks for reading Modern Data 101! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

If you have any queries about the piece, feel free to connect with the author(s). Or feel free to connect with the MD101 team directly at community@moderndata101.com🧡

Connect with Animesh on LinkedIn.

Connect with Shubhanshu on LinkedIn.

From MD101 team 🧡

With our latest community milestone, we opened up The Modern Data Masterclass for all to tune in and find countless insights from top data experts in the field. We are extremely appreciative of the time and effort they’ve dedicatedly shared with us to make this happen for the data community.

Master Modern Data, One Session at a Time!

.avif)

Animesh Kumar is the Co-Founder and Chief Technology Officer at The Modern Data Company, where he leads the design and development of DataOS, the company’s flagship data operating system. With over two decades in data engineering and platform development, he is also the founding curator of Modern Data 101, an independent community for data leaders and practitioners, and a contributor to the Data Developer Platform (DDP) specification, shaping how the industry approaches data products and platforms.

8+ years experience in Product Management. Passionate about creating data centric products providing first class user experience.

Find more community resources

Find all things data products, be it strategy, implementation, or a directory of top data product experts & their insights to learn from.

Connect with the minds shaping the future of data. Modern Data 101 is your gateway to share ideas and build relationships that drive innovation.

Showcase your expertise and stand out in a community of like-minded professionals. Share your journey, insights, and solutions with peers and industry leaders.